This table is from Statistics Canada's web site and is labeled "Wireless and radio stations in operation in Canada, March 31, 1924 to 1927. (I've only listed the items that pertain to Rough Radio's area of interest.)

|

1924 |

1925 |

1926 |

1927 |

Gov't Coast Stations |

31 |

34 |

26 |

27 |

Gov't Radio Telephone Stns. |

5 |

5 |

4 |

5 |

Gov't & Private Ship Stations |

232 |

239 |

252 |

272 |

The First Stations

In the opening years of the 20th Century the Dominion Government began a program of constructing coastal wireless stations on both the east and west coasts. The technology was new, less than 10 years old, and was still experimental to some point. For instance the ideal location for a transmitter site was at best a guess, the coverage range was a guess, and the receivers were powered by whatever energy impinged on the antenna wire.

On the West Coast the Dominion Government was concerned about the loss of life and materials and in 1906 embarked on a program of wireless (radio) station construction. Included was the building of a life saving trail along the south coast of Vancouver Island between Port Renfrew and Bamfield. A couple of manned lifeboat stations were included, the Bamfield Station the only remaining one.

The wireless stations at Victoria, Pachena, and Estevan covered the west coast of Vancouver Island, while Point Grey (Vancouver) and Cape Lazo (Comox) managed the inside waters between the island and the mainland. See a Google Earth link here.

50,113 messages were received or transmitted in 1910.

Previous to any station installation activity out on this coast, the Marconi Company had installed a number of coastal stations on the Atlantic coast. The capital cost, staffing, operation and maintenance were all born by the Company. The Marconi Company made their money by charging an amount of money per word in the telegram.

At that time the Marconi Company had an irritating policy of communicating only with Marconi fitted vessels or stations. Thus a vessel fitted with a Telefunken transmitter would not be answered by a Marconi shore station. The Government wisely felt this Marconi policy would not be in the best interests of the shipping concerns on the west coast and so installed equipment manufactured by Shoemaker. Any station using equipment fitted by any manufacturer could pass messages using the west coast stations. This included Marconi ship stations if they desired.

At this time there was only one vessel on the coast fitted with wireless. The "SS Camosun" was fitted with Marconi apparatus in July 1907. Thus the Camosun could not exchange message traffic with any of the west coast stations and eleven months later removed the equipment.

Marconi Company huffed and puffed, waving what they thought was an iron clad contract giving them a monopoly to supply and man Government stations.

A news item in October of 1926 reports Marconi was still operating the eastern stations. West coast operators were, at the start and continued to be, all Department of Marine and Fisheries staff.

By 1911 the West Coast stations were re-fitted with higher power Marconi apparatus with the intent of increasing each station's working radius. Each station had duplicate equipment, dual 6 HP gasoline engine, dual spark transmitters and two sets of generators. By this date the Marconi Company had retracted their communication policy and would accept traffic from any and all stations.

Landline Telegraphs

Landline telegraphy came with the railroads. Communication was critical for safe operation of a railway and the wire was strung on poles next to the tracks.

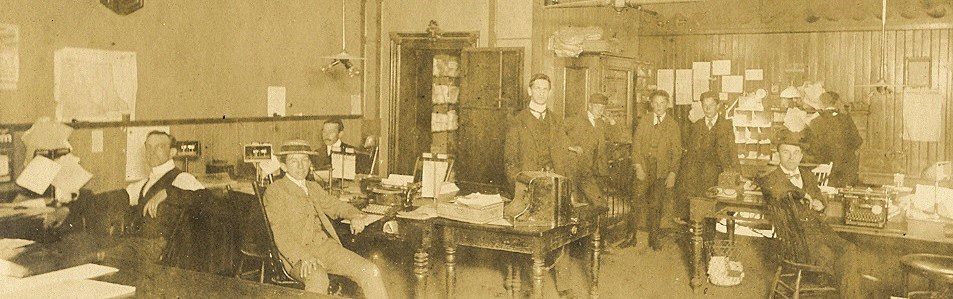

The banner photo is likely the Canadian Pacific Railway's landline telegraph office at Victoria, British Columbia in the period 1905-15.

Note the telegraph 'sounders' in the elevated boxes next to the heads of the two telegraphers on the left. The railroad's rails never did make it to Victoria but the CPR services certainly did in the form of the trans-Pacific Empress steamers, coastal steamers, the Empress Hotel in Victoria and of course, the telegraph system. A customer could walk into a C.P.R. prairie whistle stop station and purchase a ticket to any place the transportation company went. For instance get on the train in Moose Jaw and eventually disembark from an Empress liner in Hong Kong, all on the same ticket!

The landline code consisted not of beeps or tones as with a wireless/radio, but the spaces between clicks as the circuit was opened and closed by the operator at a remote station using Morse Code to key the circuit. The on again, off again current flowed through a coil of wire in the sounder box creating a fairly weak magnetic field which pulled at a spring loaded soft iron clapper. Thus there would be a click each time the remote telegrapher tapped his key. The sounder was mounted in an elevated box firstly to bring it nearer the operator's ear, and secondly to make the clicks more pronounced in a noisy room.

In the banner photo above, in the right background are three telegram runners. No doubt their bicycles are outside and waiting to take the boys and telegrams to the recipients. They were the equivalent to today's bicycle couriers.

In those days telephone systems were in their infancy and served only the local community. Convenient long distance calling was some years into the future. Canada had been spanned with telegraph wire when the Canadian Pacific Railway was completed in the 1880's. Undersea cables connected the continents together. Thus telegrams were a vital and quick communication tool for messaging between towns and countries.

In the fiscal year 1909-10 these five stations handled 18,469 messages containing 265,414 words. A year later the count 43,919 messages and some 527,588 words.

A wireless fitted vessel could now sail the coast knowing the weather conditions ahead, receive messages from their agents to pick up cargo or passengers, send a message to have supplies awaiting, and if anything did go wrong, call for help immediately. Passengers could send and receive telegrams and thus not be out of contact with their families or companies. Turned out that passengers and cargo shippers in those early days would prefer to purchase a ticket on a vessel fitted with wireless over a vessel not fitted. Steamship companies responded accordingly and within a span of about 10 years all major coastal vessels were fitted with wireless.

In 1924 the Dominion Government was considering placing the west coast stations into the hands of the Marconi Company, but nothing came of it.

By 1928 all the spark transmitters had been retired, replaced by vacuum tube equipment although some stations kept them for backup purposes.

In addition to message handling, each station was required to send a weather report containing the temperature, barometer, wind strength and direction and general weather conditions. The weather observation time was 8 AM, Noon, and 6 PM. Stations reported any vessels sighted and the time, plus any vessels they had worked providing location and the time. This intelligence was supplied to weather forecast offices and also printed in coastal news papers.

In 1938 the weather reporting became more professional and detailed as the meteorological branch at all the stations. Observations were taken every six hours starting at 00 hours GMT and sent to the Vancouver weather office.

It appears that before June 1911 no commercial traffic was passed between stations or vessels. After that date it was permitted. $1.20 for the first ten words and 12 cents for each addtional for messages to/from vessels. Ship's business rates were lower at 50 cents and 3 cents. ($1 in 1912 had the purchasing power of about $33 today.)

Oddly, passenger ships on the triangle route (Victoria, Seattle and Vancouver) were charged 25 cents and 1 cent.

These costs may have been only the coast station charges. Eventually additional charges were added for the cost of running the ship station and landline telegraph charges.

Coast Station

Introduction